$100 Billion Chinese-Made City Near Singapore 'Scares the Hell Out of Everybody'

Planeloads of buyers fly in as condos rise from the sea

Photographer: Ore Huiying/Bloomberg

Scale models of Country Garden's Forest City project on display in Johor Bahru, Malaysia.

The landscaped lawns and flowering shrubs of Country Garden Holdings Co.’s huge property showroom in southern Malaysia end abruptly at a small wire fence. Beyond, a desert of dirt stretches into the distance, filled with cranes and piling towers that the Chinese developer is using to build a $100 billion city in the sea.

While Chinese home buyers have sent prices soaring from Vancouver to Sydney, in this corner of Southeast Asia it’s China’s developers that are swamping the market, pushing prices lower with a glut of hundreds of thousands of new homes. They’re betting that the city of Johor Bahru, bordering Singapore, will eventually become the next Shenzhen.

“These Chinese players build by the thousands at one go, and they scare the hell out of everybody,” said Siva Shanker, head of investments at Axis-REIT Managers Bhd. and a former president of the Malaysian Institute of Estate Agents. “God only knows who is going to buy all these units, and when it’s completed, the bigger question is, who is going to stay in them?”

The Chinese companies have come to Malaysia as growth in many of their home cities is slowing, forcing some of the world’s biggest builders to look abroad to keep erecting the giant residential complexes that sprouted across China during the boom years. They found a prime spot in this special economic zone, three times the size of Singapore, on the southern tip of the Asian mainland.

The Forest City project will span four artificial islands.

Photographer: Ore Huiying/Bloomberg

The scale of the projects is dizzying. Country Garden’s Forest City, on four artificial islands, will house 700,000 people on an area four times the size of New York’s Central Park. It will have office towers, parks, hotels, shopping malls and an international school, all draped with greenery. Construction began in February and about 8,000 apartments have been sold, the company said.

It’s the biggest of about 60 projects in the Iskandar Malaysia zone around Johor Bahru, known as JB, that could add more than half-a-million homes. The influx has contributed to a drop of almost one-third in the value of residential sales in the state last year, with some developers offering discounts of 20 percent or more. Average resale prices per square foot for high-rise flats in JB fell 10 percent last year, according to property consultant CH Williams Talhar & Wong.

Country Garden, which has partnered with the investment arm of Johor state, launched another waterfront project down the coast in 2013 called Danga Bay, where it has sold all 9,539 apartments. China state-owned Greenland Group is building office towers, apartments and shops on 128 acres in Tebrau, about 20 minutes from the city center. Guangzhou R&F Properties Co. has begun construction on the first phase of Princess Cove, with about 3,000 homes.

Country Garden said in an e-mail it was “optimistic on the outlook of Forest City” because of the region’s growing economy and location next to Singapore. R&F didn’t respond to questions about the effects of so many new units and Greenland declined to comment.

Singapore Draw

“The Chinese are attracted by lower prices and the proximity to Singapore,” said Alice Tan, Singapore-based head of consultancy and research at real-estate brokers Knight Frank LLP. “It remains to be seen if the upcoming supply of homes can be absorbed in the next five years.”

The influx of Chinese competition has affected local developers like UEM Sunrise Bhd., Sunway Bhd. and SP Setia Bhd., who have been building projects around JB for years as part of a government plan to promote the area. First-half profit slumped 58 percent at UEM, the largest landowner in JB.

A decade ago, Malaysia decided to leverage Singapore’s success by building the Iskandar zone across the causeway that connects the two countries. It was modeled on Shenzhen, the neighbor of Hong Kong that grew from a fishing village to a city of 10 million people in three decades. Malaysian sovereign fund Khazanah Nasional Bhd. unveiled a 20-year plan in 2006 that required a total investment of 383 billion ringgit ($87 billion).

Singapore’s high costs and property prices encouraged some companies to relocate to Iskandar, while JB’s shopping malls and amusement parks have become a favorite for day-tripping Singaporeans. In the old city center, young Malaysians hang out in cafes and ice cream parlors on hipster street Jalan Dhoby, where the inflow of new money is refurbishing the colonial-era shophouses.

Outside the city, swathes of palm-oil plantations separate isolated gated developments like Horizon Hills, a 1,200-acre township with an 18-hole golf course.

“The Chinese developers see this as an opportunity. A lot of them say Iskandar is just like Shenzhen was 10 years ago,” said Jonathan Lo, manager of valuations at CH Williams Talhar & Wong, a property broker based in Johor Bahru. “Overseas investors coming to Malaysia is a new phenomenon so it’s hard to predict.”

Construction soon outpaced demand. To sell the hundreds of new units being built every month, some companies took to flying in planeloads of potential buyers from China, prompting low-cost carrier AirAsia Bhd. to start direct flights in May connecting JB with the southern Chinese city of Guangzhou.

On the first such flight, 150 of the 180 seats were taken by a subsidized tour group organized by Country Garden. Almost half of them ended up buying a residence, the developer said in an e-mail.

Potential buyers at the Country Garden sales office.

Photographer: Ore Huiying/Bloomberg

Buses disgorging Chinese tourists at Forest City in November were met by dozens of sales agents, with the women dressed in traditional Sarong Kebaya outfits similar to those worn by Singapore Airlines Ltd. stewardesses.

The visitors filed into a vast sales gallery where agents explained the enormity of the project using a replica of the finished town, with model buildings as tall as people. They viewed show flats with marble floors and golden-trimmed furniture, dined on a buffet spread and were encouraged to sign on the spot. A two-bedroom apartment cost as little as 1.25 million yuan ($181,400), about one-fifth of the price of a similar-sized private apartment in central Singapore.

But JB is not Shenzhen. The billions poured into the economic zone in southern Guangdong in the 1980s and 1990s by Hong Kong and Taiwanese firms was soon dwarfed by Chinese investment as factories sprang up all along China’s coast.

In Malaysia, investment growth is slowing, slipping to 2 percent year on year in the third quarter, from more than 6 percent in the previous quarter. The value of residential sales in Malaysia fell almost 11 percent last year, while in Johor the drop was 32 percent, according to government data.

“I am very concerned because the market is joined at the hip, if Johor goes down, the rest of Malaysia would follow,” said Shanker, at Axis-REIT Managers, who estimates that about half the units in Iskandar may remain empty. “If the developers stop building today, I think it would take 10 years for the condos to fill up the current supply. But they won’t stop.”

Ongoing construction of the Country Garden Danga Bay project.

Photographer: Ore Huiying/Bloomberg

Property Pipeline

Developers have a pipeline of more than 350,000 private homes planned or under construction in Johor state, according to data from Malaysia’s National Property Information Centre. That’s more than all the privately built homes in Singapore. Forest City could add another 160,000 over its 30-year construction period, according to Bloomberg estimates, based on the projected population.

“Land is plentiful and cheap,” said Alan Cheong, senior director of research & consultancy at Savills Singapore. “But buyers don’t understand how real estate values play out when there is no shortage of land.”

The developers haven’t been helped by government measures designed to prevent overseas investors pushing up prices. In 2014, Malaysia doubled the minimum price of homes that foreigners can buy to 1 million ringgit, and raised capital gains tax to as much as 30 per cent for most properties resold by foreigners within five years.

The stream of new developments has scared away some investors, pushing developers to concentrate more on finding families who will live in the apartments, said Lo at CH Williams. Profit margins have fallen to around 20 percent, from 30 percent when land was cheap a few years ago, according to his firm.

Ongoing construction of the Tropicana Corp's Danga Bay project.

Photographer: Ore Huiying/Bloomberg

Singapore billionaire Peter Lim’s Rowsley Ltd. said last year it will no longer build homes in Iskandar and will instead turn its Vantage Bay site into a healthcare and wellness center.

“The Chinese players have deep financial resources and are building residential projects ahead of demand,” Ho Kiam Kheong, managing director of real estate at Rowsley said in an interview. “If we do residential in Iskandar, we would be only a drop in the ocean. We can’t compete with them on such a large scale.”

UEM Group Bhd., the biggest landowner in Iskandar, is selling plots to manufacturers to boost economic activity in the area.

A Country Gardens ad outside the sales gallery.

Photographer: Ore Huiying/Bloomberg

“Industries are the queen bee,” creating jobs and wealth for local residents, said Chief Executive Officer Izzaddin Idris. “That will bring a demand for the houses we are building.”

U.S.-based chocolate maker Hershey Co. is among those building a plant in Iskandar, joining tenants such as amusement park Legoland Malaysia and Pinewood Iskandar Malaysia Studios—a franchise of the U.K.-based movie studio.

Meanwhile, sales reps sell a Utopian dream—a city of the future with smart, leafy buildings and offices full of happy, rich residents.

“It will take a while for all the parts to fall into place: infrastructure, manufacturing, education, healthcare and growth in population,” said Ho at Rowsley. “But I have no doubt it will happen eventually.”

—With assistance from Emma Dong.

—With assistance from Emma Dong.

Read These Next:

Confessions of an Instagram Influencer

I used to post cat photos. Then a marketing agency made me a star.

I’ve always been well-liked. At least, I think that’s the case. I have friends, a spouse, a job, a college degree. I exercise. I get haircuts regularly.

And yet lately I’ve felt unrealized—incomplete, almost. Everywhere I look on social media, I’m surrounded by extremely attractive, superbly groomed men and women who eat meals that are not only healthy but impeccably plated. My clothes seem tired, wrinkled, bereft of accessories. And my vacation photos—Christ, my vacation photos.

I should mention I’ve been spending a lot of time on Instagram, the app for sharing photos that is also, according to sociologists and my own experience, a perfectly designed self-esteem subversion service. Whereas Snapchat encourages users to create rainbow-vomit selfies that disappear after 24 hours, Instagram’s sleek design and flattering filters encourage its more than 500 million users to sexify their landscapes and soften their harshest features. It helps them turn snapshots into something out of the glossy pages of a lifestyle magazine.

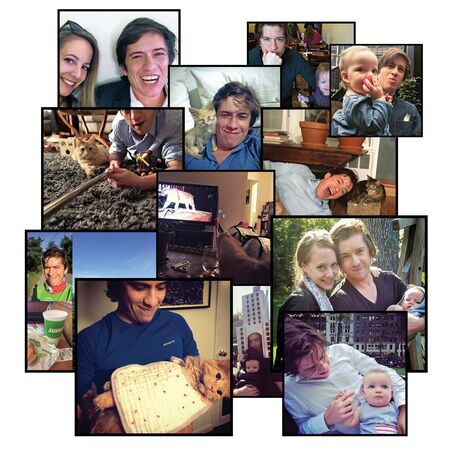

Before, Chafkin’s account featured normal, everyday photographs.

Source: Instagram

Because of this—and because advertising budgets will inevitably flow to any medium where large numbers of people are spending large amounts of time—Instagram has attracted a sort of professional class. These “influencers,” as they’re known, are media properties unto themselves, turning good looks and taste into an income stream: Brands pay them to feature their wares. Look a little more closely at your Instagram feed, and you’ll probably notice that attached to the post of the gleaming hotel lobby, the strappy heels, the exquisitely berried breakfast is a sea of hashtags—among them, #ad or #sp, which discreetly disclose that these are in fact sponsored posts.

There are thousands, perhaps tens of thousands, of influencers making a living this way. Some make a lot more than a living. The most successful demand $10,000 and up for a single Instagram shot. Long-term endorsement deals with well-known Instagrammers, such as Kristina Bazan, who signed with L’Oréal last year, can be worth $1 million or more. Big retailers use influencers, as do fashion brands, food and beverage companies, and media conglomerates. Condé Nast, publisher of the New Yorker and Vogue, recently announced that it would ask IBM’s artificial intelligence service, Watson, to take a break from finding cancer treatments to identify potential influencers.

Earlier this year, on the marketing website Digiday, an anonymous social media executive ranted that marketers were essentially throwing money away on influencers, whom the ranter characterized as talentless. That made me curious, and I started asking around to understand just how hard this job really is. Some swore the work is difficult. “If it was so easy to be an influencer, then every single person on earth would do it,” said Gary Vaynerchuk, who parlayed a YouTube channel into an ad agency, VaynerMedia, that specializes in social media marketing and now employs about 750 people. But another influencer guru, Daniel Saynt of the agency Socialyte, disputed that. With the right guidance, he said, almost anyone could Instagram professionally. To prove it, he made me an offer: He’d help me become an influencer myself.

The plan, which I worked out with my editor and a slightly confused Bloomberg Businessweek lawyer, was this: With Saynt’s company advising me, I would go undercover for a month, attempting to turn my schlubby @mchafkin profile into that of a full-fledged influencer. I would do everything possible within legal bounds to amass as many followers as I could. My niche would be men’s fashion, a fast-growing category in which I clearly had no experience. The ultimate goal: to persuade someone, somewhere, to pay me cash money for my influence.

In late September, two weeks before the experiment was slated to begin, I reported to Socialyte’s headquarters in New York’s SoHo neighborhood. The agency manages 100 or so Instagram personalities, taking 30 percent of their bookings in exchange for setting them up with gigs. Many of these clients have millions of followers, and Saynt won’t talk to you unless you have about 100,000, but he agreed to make an exception for me and my 212. Saynt, a big man with a soft voice who wears an expression of perpetual amusement, greeted me with a hug and apologized for being a little lethargic. “I’m on a detox,” he said, adding that the previous week—Fashion Week in New York—he’d been on a seven-drink, pack-a-day bender. He mostly stayed quiet as Beca Alexander, his ex-wife and Socialyte’s president, and Misty Gant, the vice president for talent, peppered me with advice.

Instagram-ready grooming.

Photographer: Amy Lombard for Bloomberg Businessweek

I needed a haircut, for sure, and would have to keep my fingernails clean. Socialyte would suggest a photographer for me to hire, and I was told to bring 20 or so mix-and-match outfits to a shoot, to generate a huge volume of “looks” to post each day.

“So,” Gant asked me, “what brands do you wear?”

After an awkward exchange during which I half-muttered the words “J” and “Crew,” it was decided that I couldn’t be trusted to dress myself. Saynt and his team would find brands willing to lend me clothes and would enlist a couple of influencers to help me put ensembles together. I would bring essentially nothing to the table. “You don’t have a cute dog, do you?” Alexander asked.

A week later, after a haircut the price and duration of which I refuse to share, I met Marcel Floruss and Nathan McCallum, two of Socialyte’s professional clients, at Lord & Taylor to borrow some outfits. The two men are opposites in almost every way. McCallum is compact and favors ripped jeans and piercings, and Floruss is lanky and clean-cut. Both are cartoonishly handsome, and both (I noticed this later when I checked out their Instagram work) have amazing abdominal muscles. “Constantly,” Floruss said, when I asked him how often he takes pictures of himself. “You sell part of your soul. Because no matter what beautiful moment you enjoy in your life, you’re going to want to take a photo and share it. Distinguishing between when is it my life and when am I creating content is a really big burden.”

I’d assumed two things about the beautiful people of Instagram. First, I figured they used the service the way Instagram suggests—that is, snapping pics and immediately sharing them with friends. Second, I assumed they took the photos themselves. Neither was true, as I learned when, on an unseasonably warm morning in early October, I brought 18 outfits to the Socialyte office. I met James Creel, my photographer for the day, as well as McCallum, who’d agreed to offer me styling tips, and his own regular photographer, Walt Loveridge, who’d joined in case McCallum felt inspired to do some modeling himself. The plan, as we trooped out the door into SoHo, was to shoot all the looks in a single day. “Let’s go find some walls,” Creel said.

The basic formula for most influencer portraits involves standing in front of a textured backdrop—usually a wall that’s brick or painted in some stylish way—and looking off, unsmiling, into the middle distance. Creel, who works as a personal trainer when he’s not shooting Instagram models, asked me to step out from doorways, so he could capture me paparazzi-style. He constantly asked me to run my fingers through my hair, and I was forced, for several hours I think, to rock onto and off of curbs, as if I were charismatically jaywalking. We ended up needing a second day. At one point during our 12 or so hours together, after I’d successfully walked in between taxis (primo color pop) and pursed my lips, Creel lowered his camera and offered a sincere compliment: “That was a great moment.”

I posted my first picture around noon on a Sunday morning—a relatively conservative three-quarter-length shot, in which I perform a sultry lean against a chain-link fence in a plaid Perry Ellis bomber jacket. Appearing incongruously atop my previous photos—the utterly ordinary postings of a new dad—it didn’t get a digital “like” for 15 minutes. That pace didn’t bode well. Moderately successful influencers might get 100 likes or more in that period, and as I tried to focus on supervising my year-old daughter’s play date, I was getting worried.

I probably should have anticipated this. Part of what makes Instagram valuable to advertisers is that there aren’t many shortcuts to accruing an audience. Unlike Twitter, for instance, where a clever quip can be quickly retweeted, bringing a deluge of followers, Instagram is relatively resistant to viral growth. Pretty much the only way you can add to your flock is if someone happens on your profile, likes what he sees, and decides to follow you.

How do you get people to discover you? Your best hope is to use hashtags—that is, sticking a pound sign in front of a keyword to make it easier for users searching for a specific type of photo to find you. There’s something tacky about using #liveauthentic, which has been deployed more than 14 million times, to get strangers to look at pictures that essentially amount to advertisements, but every influencer I spoke with assured me that hashtags worked, so hashtags it would be. Saynt recommended that I include at least 20 with every post.

Included in The New Money Issue of Bloomberg Businessweek, Dec. 5-Dec. 11, 2016. Subscribe now.

Photographer: Amy Lombard for Bloomberg Businessweek

To avoid looking totally desperate, I hid my hashtags below a series of line breaks. To avoid any unnecessary creativity, I used an app, Focalmark, which allowed me to input a couple of variables about each shot—for instance that it was a portrait, containing menswear, in New York City—and would then spit out a list of hashtags. They were so embarrassing that I tried not to read them before sticking them in my Instagram feed. But here are a few that I used regularly: #menwithclass, #mensfashion, #agameofportraits, #hypebeast, #featuredpalette, #makeportraits, #humaneffect, #themanity, and, of course, #liveauthentic.

By dinnertime, I’d posted a second picture and had acquired a few dozen likes and roughly three followers. That’s actually not bad for somebody with an almost nonexistent presence on Instagram, but it was discouraging to me, because I would need at least 5,000 followers to have any hope of making money. That night, I signed up for a service recommended to me by Socialyte called Instagress. It’s one of several bots that, for a fee, will take the hard work out of attracting followers on Instagram. For $10 every 30 days, Instagress would zip around the service on my behalf, liking and commenting on any post that contained hashtags I specified. (I also provided the bot a list of hashtags to avoid, to minimize the chances I would like pornography or spam.) I also wrote several dozen canned comments—including “Wow!” “Pretty awesome,” “This is everything,” and, naturally, “[Clapping Hands emoji]”—which the bot deployed more or less at random. In a typical day, I (or “I”) would leave 900 likes and 240 comments. By the end of the month, I liked 28,503 posts and commented 7,171 times.

Most committed influencers, including Socialyte’s clients, use bots in one way or another, but it should be said that this is an ethical gray area. Instagram doesn’t explicitly ban bots, but its terms of service do prohibit sending spam, which, when viewed in a certain light, is exactly what I was doing. On the other hand, except for a single user who somehow had me pegged and accused me of being a bot, nobody with whom I interacted seemed to mind the extra likes or comments. In fact, most of them would respond immediately with comments of their own. “Thanks dude!” they’d say. Or they’d simply give me a “[Praying Hands emoji].” I got hundreds of comments like this.

By the time I fell asleep that first night, I was getting a steady stream of likes and adding a new follower every couple of hours. By morning my post had more likes than anything I’d ever put on Instagram, including a shot in which I was holding my newborn daughter. In the picture, which my wife snapped from the end of the hospital bed, I’m lying back with my eyes closed, blissed-out and exhausted. It’s the best, most honest picture anyone has ever taken of me, and it has half as many likes as that shot of me in the bomber jacket on the chain-link fence.

Socialyte had suggested I create three posts a day, which sounds easy since I already had most of the pictures I would need. It was not easy—and I spent much of the next month in a state of constant dread, mostly because I hadn’t told my friends or family members about my Instagram experiment. After my mom gently inquired about, as she put it, “your male modeling career,” and I told her I was working on a story, she let out a sigh. “Oh,” she said. “I was worried there was some massive insecurity going on.” My baffled friends also had questions. “First, you look boss. Congrats,” my friend Dave wrote in a comment. “Second, what is going on?”

Another difficulty was that I’d been told to post at least one piece of “lifestyle content”—that is, a picture of something other than myself—every day. In general, pictures of people get more likes than anything else, but the idea was to create a sense of variety and to avoid boring my new audience. Alexander suggested sunsets, cityscapes, and food. “You don’t have to eat it,” she offered. “Just make it pretty.”

I did my best, ordering fancy cocktails I wouldn’t normally drink and trying to eat items, like avocado toast, I’d seen on Instagram. It was not enough. A week into our experiment, Alexander and Saynt informed me, in the gentlest manner possible, that my lifestyle content was terrible.

The natural solution was professional help. Alexander introduced me to Alisha Siegel, a wedding photographer by trade who also sells stock images to influencers. Siegel could offer me as many perfectly framed lattes, hipster hotel lobbies, and urban sunsets as I wanted. I bought 20 for $400, which brought my total tab for photography services to $2,000. I asked her about credit—should I note in my feed that she was the photographer? Siegel suggested that I might shout her out once or twice, but crediting her would break the illusion. As she pointed out, “You’re the one who is supposed to be experiencing these things.”

Armed with my lifestyle content, I felt a surge of confidence. I was adding 20 to 30 followers most days, up from 10 a day in the first week. When one of my friends asked me about a breakfast shot—specifically, what the hell was that yellow blob on top of my granola?—I evaded and moved on. (Citrus curd.) It no longer seemed weird that all day and all night my virtual double was doling out likes and saying things like “High five for that!” about pictures I had not seen and would never see.

By the end of Week Two, I’d reached 600 followers, or a threefold increase. Saynt told me he thought that if I kept it up, I could be at 10,000 by the end of the year, which would be enough to command maybe $100 per sponsored post. That was encouraging. But to keep up the pace, I’d have to spend $2,000 a month on photography services and also find a way to keep a steady stream of new outfits coming. There was no way I would ever break even on this; I clearly didn’t have the talent.

On the other hand, I was already verging into “micro-influencer” territory, a hot new field within influencer marketing where, rather than hiring one or two big-time influencers, an ad agency will simply give out free merchandise to 50 small-timers. Micro-influencers are “a core piece of our strategy,” according to Dontae Mears, a marketing manager at VaynerMedia. “You find the engagement is stronger. The trust is better. And you don’t necessarily have to pay them.”

The breakthrough came as my follower count pushed above 800. I got a message from Andrew Hurvitz, a photographer in Los Angeles and the founder of Marco Bedford, a clothing line. “You want to collaborate?” he wrote. I was ecstatic.

A few days later, one of his T-shirts was sitting in my mailbox. I pleaded with my wife—who had come to despise my transformation—to follow me outside on a Sunday evening with our digital camera. I wore my coolest jacket. I looked, wistfully, to my left. I ran my fingers through my influencer haircut. The picture did pretty well, earning 156 likes and, according to Instagram, reaching 468 people. As an official spokesman for Marco Bedford (#ad #sp #liveauthentic), I feel compelled to say that I stand by my characterization that Hurvitz’s shirt, which retails for $59, is “beautiful.”

My experiment was winding down, but I’d begun to wonder whether there might be an easier way to do all this. The internet is full of services that purport to deliver followers by the thousands. Buying followers—or buying likes and comments, which are also for sale online—won’t trick sophisticated advertisers, because Instagram reports actual impressions and audience size. But the tactic can help make your profile look a little more impressive. There was a chance that a fake boost could turn into genuine momentum. And so, with a week or so left until my deadline, I logged on to a site called Social Media Combo, which promises “high quality followers.” Packages range from $15 for 500 to $160 for 5,000. Not wanting to gild the lily—and slightly concerned about corporate AmEx card ramifications—I went for the base package.

For two days, nothing happened. Then, without warning, I jumped from 885 followers to about 1,400 in a matter of hours. By the time I posted my final influencer photo—a lifestyle shot of a flower shop that Siegel had sold me—on Nov. 11, Instagram had removed a bunch of my new fake admirers, but I was adding enough followers to mostly offset the drop-off. As I write this, I’m back up to almost 1,400. According to FollowerCheck, an app that purports to analyze an Instagram account for authentic engagement, 1,168 of my followers are real. I’m afraid to look to see how many of my actual friends have unfollowed me.

I quit posting the following day, a Saturday, and didn’t put anything on Instagram for a full week. There were moments when that made me anxious—I still have a killer shot of myself in a camel-hair coat that’s perfect for #autumn—and I started asking my fellow influencers what they thought I should do with my newfound fame. “I wouldn’t throw it away,” offered Yena Kim, the creator of the Instagram account Menswear Dog, which has 288,000 followers. “You should turn it into this dapper writer guy.”

Getting ready for the paparazzi.

Photographer: Amy Lombard for Bloomberg Businessweek

Kim, a former designer for Ralph Lauren, told me she started her account as a sort of joke, too, posting photos of her shiba inu in men’s sweaters and sport coats in the style of other popular fashion influencers. Now her dog, Bodhi, is a business and is represented by a special influencer pet agency, Wag Society. (The company is owned, improbably, by the New York Times Co. and boasts 150 clients, including hedgehogs, cats, and a potbellied pig named Esther.) “Whatever you do in life, it helps to have a following,” Kim said. “It’s going to help you professionally.”

I am not and never will be Dapper Writer Guy. But I think she’s probably right. I should keep going. As I wrote that last paragraph and prepared to mail Hurvitz his shirt back, I took another picture, an authentic one. It showed a desk—a horrible, embarrassing mess of a desk, with a paper plate and empty disposable cups and stacks of old magazines.

But as I went to post it, I hesitated, and had a thought: Wouldn’t this look a little better with a filter?

No comments:

Post a Comment